Basic Bayesian Statistics

Bayes’s Theorem

I am an ancestral Minnesota Twins fan, having grown up in Minnesota during the glory days of the M&M boys, Johan Santana, and Ron Gardenhire. Back then, the Twins won a lot of games, just…not during the postseason. In fact, the Twins have never had much success in October, making the playoffs only 14 times out of 61 seasons. In that time, they’ve compiled a 25-44 record, which is not good, but given that they’re always playing the best teams in the playoffs, it’s not horrific. Unfortunately, most of those losses have come since the last time they won the World Series in 1991, and shockingly, 16 of them are to a single team: the New York Yankees, who they’ve beaten exactly twice in that time.

So, let’s say you’re a Twins fan, and you’re excited that your team has made it to the playoffs, and you don’t yet know what team they’ll be facing, but it could be the Yankees. What is the probability that the Twins will win the first game they play? The most straightforward way to predict this is to assume that current trends will hold: they will probably lose (25/(25+44) = 36% chance of winning), but they are much more likely to lose if they are playing the Yankees (2/(2+16) = 11% chance of winning). Bayes’s theorem is a theorem invented by Thomas Bayes (shock) and refined and published by Richard Price that provides a formalism for this kind of conditional thinking. It starts with the idea of a “conditional probability”, or in our example, what is the probability that the Twins are going to win a playoff game given that we know they are playing the Yankees?

\[\begin{align*} P(W|Y) = \frac{P(W\cap Y)}{P(Y)} \end{align*}\]That equation essentially reads “The probability ($P$) that the Twins will win ($W$) if they are playing the Yankees ($Y$) is the same as the fraction of playoff games where the Twins have played and beaten the Yankees ($P(W\cap Y)$)1 divided by the fraction of playoff games the Twins have played against the Yankees ($P(Y)$).”

Let’s say you missed the game and didn’t even know who the Twins were playing, but you hear the next day that the Twins won. You might then ask yourself (if you are a nerd), “Given that I know the Twins won their game last night, what is the probability it was against the Yankees?” In that case the equation would be:

\[\begin{align*} P(Y|W) = \frac{P(W\cap Y)}{P(W)} \end{align*}\]A.k.a.: “The probability that the Twins were playing the Yankees, given that I know they won last night, are the same as the number of times the Twins have played and beaten the Yankees divided by the number of playoff games the Twins have ever won.”

If you’re perceptive you might notice that $P(W\cap Y)$ appears in both equations. We can solve for $P(W\cap Y)$ in one equation and stick it into the other, arriving at Bayes Theorem:

\[\begin{align*} P(W|Y) = \frac{P(Y|W) P(W)}{P(Y)} \end{align*}\]This is a slightly more confusing equation that reads “The probability that the Twins win their playoff game given that it is against the Yankees, is the same as the probability that the Twins played the Yankees given that we know they won that game, multiplied by the fraction of playoff games the Twins have ever won, divided by the fraction of total playoff games the Twins have played against the Yankees.”

This sentence is confusing, but isn’t really necessary to understand in detail, because the point of this equation is to use it to do statistics. Scientists most frequently use this theorem in the context of understanding how the data they get from their experiments change their model/theory of the phenomenon they are investigating.

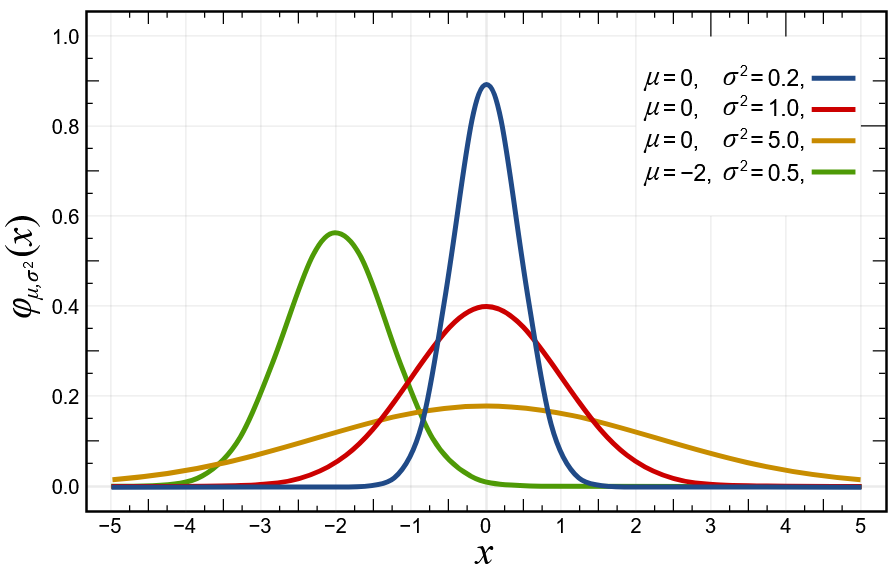

For example, let’s say you are a physicist who is studying a new particle, and you want to measure its mass. Let’s say you already have some idea of what the mass is: you have a most likely value for the mass, and some idea of how good that estimate is in the first place. You can model this understanding as a normal distribution, centered at your best estimate of the mass, and with a standard deviation that quantifies your understanding of how good the estimate is.

Now let’s say you go make 15 measurements of the mass of this particle. Bayes Theorem gives you a way to take in those measurements, and use them to “update” your model of the particle’s mass. Maybe the mean of the distribution will change, and hopefully the standard deviation will decrease (i.e. your understanding improves). To do this, Bayes Theorem tells you to compute the “likelihood” of getting the measurements given your current model of the particle mass, and multiply it by the model itself (called the “prior” distrubution). Because the final thing you are getting (the “posterior” distribution) is still a probability distribution, you then have to normalize it to 1 (this is how I understand $P(Y)$ in this example). This procedure for taking a model of something, incorporating new data, and computing the updated model given the data, is extremely powerful.

Conjugate priors

In certain situations, multiplying the prior and likelihood distributions together to get the posterior distribution can, by stroke of fortuitous math, return you a distribution with the same form as the prior distribution. This means that the mathematics of propagating likelihood information through a Bayesian model is very straightforward, and even better, can be repeated without the form of the posterior becoming a total disaster. One of these conjugate prior-posterior relationships occurs when you are trying to estimate the mean of a normal distribution.

We can return to the model from the previous section, where our physicist (you) is trying to measure the mass of a particle. The way physicists typically measure the mass of a particle is to watch it break up into other product particles, and then measure the total energy of all of the products. It turns out that, due to measurement error, and even quantum mechanics, the total energy of these products does not always add up to the exact same number, even if the starting particle is the same every time. This means that if we measure the total energy of the products a bunch of times and plot the distribution, we will get a normal distribution, where the mean represents the mass of the particle, and the standard deviation represents its decay rate, or the inverse of its half-life (i.e. a stable particle like an electron would appear ).

If we take the Bayesian approach, and say that we do not know what the mean is, but rather have a prior for it, choosing that prior distribution to also be a normal distribution will give us a conjugate prior-posterior relationship. Let’s work it out:

The mass of our particle has some value $\mu$, and the width has some value $\Gamma$. The profile of the particle is then

\[\begin{align*} P(x | \mu, \Gamma) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\Gamma^2}}e^\frac{-(x-\mu)^2}{2\Gamma^2} \end{align*}\]Our conjugate prior on $\mu$ has, in this case, the same form:

\[\begin{align*} p_0(\mu) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma_0^2}}e^\frac{-(\mu-\mu_0)^2}{2\sigma_0^2} \end{align*}\]What we need now is the likelihood, which is really similar to $P\left(x | \mu, \Gamma\right)$ but where you insert the values you have actually measured for $x$, which we’ll now call $\textbf{x} = {x_1, x_2, … x_n}$ for $n$ observations. Since we are computing the likelihood of measuring all of those observations, we will just multiply all of them together:

\[\begin{align*} L = \prod_{i=1}^{n} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\Gamma^2}}e^\frac{-(x_i-\mu)^2}{2\Gamma^2} \\ L = \frac{1}{\left(2\pi\Gamma^2\right)^{\frac{n}{2}}} e^\frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n}-(x_i - \mu)^2}{2\Gamma^2} \\ \end{align*}\]After multiplying this by $p_0(\mu)$ and refactoring, we get:

\[\begin{align*} p_1(\mu) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma_1^2}}e^\frac{-(\mu-\mu_1)^2}{2\sigma_1^2} \end{align*}\]where $\sigma_1 = \left( \frac{1}{\sigma_0^2} + \frac{n}{\Gamma^2} \right)^{-1}$ and $\mu_1 = \sigma_1 \left( \frac{\mu_0}{\sigma_0^2}+\frac{\sum_{i=1}^n x_i}{\Gamma^2} \right)$. In the limiting case where $n \rightarrow \infty$, this reduces to $\sigma_1 \rightarrow \frac{\Gamma^2}{n} \rightarrow 0$, and $\mu_1 \rightarrow \frac{\Gamma^2}{n}\frac{\sum_{i=1}^n x_i}{\Gamma^2} \rightarrow \bar{\textbf{x}}$, meaning that our estimate of $\mu$ gets arbitrarily precise over time. You can do the exact same thing if you assume that $\mu$ is known but $\Gamma$ is not, in which case the conjugate prior is an inverse-gamma distribution. If you want to place a prior on both $\mu$ and $\Gamma$ simulaneously, you can do this with a normal-inverse-gamma distribution.

-

$\cap$ is a math symbol that basically means “and”. ↩